Scientific publishing stands on a pedestal – society views scientific reports as the closest approximation to Truth that we have. Scientists themselves know that science is an attempt to converge, over decades, at an interpretation that is measured and proven to be the least wrong. Truth is out there, but we can only hope to see its shadow.

Scientific publishing stands on a pedestal – society views scientific reports as the closest approximation to Truth that we have. Scientists themselves know that science is an attempt to converge, over decades, at an interpretation that is measured and proven to be the least wrong. Truth is out there, but we can only hope to see its shadow.

Nonetheless, I desperately hope that scientific publishing continues to stand on its elevated platform. Without that, all society has is the “fair and balanced” cacophony of internet, where everyone will pick and choose whichever quackery and pseudoscience suits their particular calcification of opinion best.

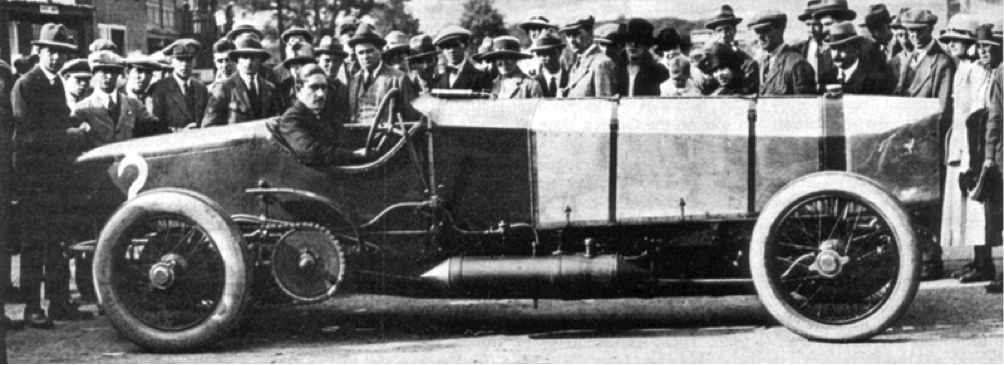

However, while science may stand on its pedestal to the public, in reality it is a magical car driven by editors and fuelled by peer review – Chitty Chitty Bang Bang!

To the best of its ability, editors and peer reviewers must establish that what gets reported as science follows sound methodology, so that it can be independently verified, and that the conclusions presented justifiably follow from the data and analysis used. Editors and peer reviewers should also establish that what gets reported as science is important – worth your time and attention as a reader.

There is a clear dissonance in the academic community: on the one hand, surveys show that there’s a broad consensus among scientists that peer review is the cornerstone of academic publishing; on the other, there’s also a widespread perception that peer review does not fulfil what is expected from it, and can actually sometimes cause problems. The ability of the traditional peer review system to deliver what is expected from it today is increasingly being challenged.

In the spirit of Peer Review Week 2015 which, as well as celebrating peer review and recognizing the significant amount of time researchers spend on it, is also an opportunity for the community to debate what’s working and what isn’t, I’d like to highlight some of the challenges – the troublesome noises of the title – and some potential solutions.

Peer review, and the gradual slide down the journal prestige ladder one rejection at a time, creates significant delay for publishing. In addition to the time spent on reviewing submissions that get accepted, scientists spend maybe 15 million hours every year reviewing submissions that get rejected – it’s not lost time because it means the filters work (if peer review always led to acceptance, it would be a miserable failure for the system), but in many cases the reports could be used to support a positive decision at another journal. Peer review is open to the risk of bias – whether nationality, institutional prestige, gender, personal relationships, or other issues really affect a given peer review and publishing decision is irrelevant. The real question is: can the author fully trust that they will not affect it? Soliciting peer reviews and chasing after missed deadlines has become a burden of silly proportions for editorial offices, eating away time from the real scientific stewardship of the journal’s aims and scope. And peer review is open to the risk of outright fraud: in the past year dozens of papers have been retracted due to fraudulent peer reviewing.

But, for me, the most significant of these challenges is the erosion of trustworthiness. The quality of peer review simply varies too much, without any effective assessment of that quality and procedures to bring those assessments to bear on publishing decisions.

Under the current system, there’s arguably little incentive for a researcher to bring significant investment of time and his or her full attention and expertise to bear on a peer review task. I believe that the lack of recognition for peer review – and the time it takes – means that many scientists are content with doing it quickly, not carefully. Yet a good or bad peer review may literally decide the fate of some young researcher’s entire career. How many bright young people has science lost, simply because of a hasty and careless peer review prevented publication of an important manuscript just before a crucial grant deadline, prompting them to give up?

It kind of lost me. But I still love Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.

Hence my new job: building a refinery to develop a higher-octane fuel.

At Peerage of Science we are taking a two-pronged approach to improving peer review (neither of which are proprietary, so nothing prevents journals that do not use Peerage of Science from implementing these on their own instead.

First, open engagement – as long as your identity and qualification have been validated by a trustworthy external source, and you’re not affiliated with the authors via institution or recent co-authorship, you can engage to peer review any manuscript. Editors are welcome to recommend reviewers but do not hold exclusive right to do so – any Peer, including the authors, can recommend anyone else. Second, the reviews themselves are peer reviewed (“peer-review-of-peer-review”). This creates a very effective social pressure for researchers to put more time and effort into doing peer review work carefully. In addition, the default approach to anonymity in Peerage of Science is triple-blind, meaning that everyone’s arguments – authors, reviewers, editors – must stand on their own scientific merit, affected as little as possible by biases against or for personal factors. However, while this is the default, rather than mandating a particular view, Peerage of Science lets the author choose.

As a member organization of ORCID, Peerage of Science is also looking forward to supporting the new standardized, citable and resolvable records for peer reviewing work in ORCID profiles. It is important that peer reviewing work gets recognised in a way that takes the quality of the work into account, and having an authoritative record that is linked to cross-evaluation results and feedback is a promising way to make this happen.

Many other organizations are, like us, working on improving the peer review system, whether by facilitating recognition for the work of peer reviewers, by experimenting with new forms of peer review, by finding ways to reuse reviews of rejected papers, and more. So, when celebrating Peer Review Week – now and in the future – let’s all try to make peer review something that justifies the pedestal, and keeps Chitty Chitty Bang Bang flying, 52 weeks every year.

[Image caption: Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. Count Louis Zborowski with Chitty Bang Bang 1 at Brooklands c1921. Public domain image via Wikipedia.]