This post was co-authored with Christopher Brown and Neil Jacobs (Jisc), Josh Brown and Laure Haak (ORCID), and Clifford Tatum (SURF)

The landscape of research information is largely closed to us. We rely on original research to solve many of the challenges facing humanity, to improve lives, and to advance human understanding, and we invest in it accordingly. However, when we survey the map of our research world it is filled with gaps. We pass along a few well-trodden roads (too often paying a substantial toll for the privilege) and we can only wonder about what lies just over the horizon.

The landscape of research information is largely closed to us. We rely on original research to solve many of the challenges facing humanity, to improve lives, and to advance human understanding, and we invest in it accordingly. However, when we survey the map of our research world it is filled with gaps. We pass along a few well-trodden roads (too often paying a substantial toll for the privilege) and we can only wonder about what lies just over the horizon.

We can point to many contributing factors: business models that militate against the sharing of information; aggregation of research analytics for local strategic purposes; technological barriers to linking information between sources; cultural practices that reward and privilege a small slice of research activity; and systems that emphasise hard sciences and anglophone literature. Any and all of these can, and do, hide some of the richness of research endeavour. However, these systemic challenges are not the focus of this discussion. Instead, our focus is on the gaps in our understanding of the landscape: the empty parts of the research map.

If we are to open research up, to enable and support more transparency and accountability, and to ensure that we are supporting research effectively, we must be able to survey the research landscape in its entirety. That means recognising more kinds of contributions to research, and acknowledging a broader, more diverse range of career paths. To do so, we need tools to help us to fill in the blanks. Luckily, a powerful set of these tools exists – open, community-governed identifier systems are already a well-established part of the scholarly world.

Identifiers act as coordinates on the research map. They both tell us where something is located, and also act as signposts, guiding us to information sources and helping us to discover connections between people, ideas, organisations, funding, employment, publications, activities, and more. When a researcher shares an idea or makes a contribution, an identifier can be used to mark its existence. The information connected to that identifier can tell us about its creator(s), the nature of their contribution, the previous work that underpins it, and its impact on subsequent research and outcomes.

Describing a landscape helps us understand the terrain better, but it does not necessarily mean the end of privacy or ‘ownership’ of a part of the land itself. Some information will be personal, competitive, or simply a work in progress. To manage access to that information in a way that can balance the needs of the whole community, while protecting the interests of individual researchers and the organisations that support them, it can be enough simply to provide a signpost. In this way, we can know that the information exists, where it is kept, and who to ask for access to it, if that is appropriate. These signposts have the potential to fill many of the gaps in our knowledge of the research landscape, to expose fruitful connections, and to help us to better understand the overall map.

However, this potential is not currently being achieved. Although we increasingly embed identifiers in works and in our information systems, we don’t do so comprehensively or consistently. We need research organisations and researchers alike to understand the value of identifiers, and to commit to using them appropriately and effectively.

We are not suggesting that everything, everywhere should have an identifier. We don’t want to spend precious time and energy building up a special identifier system for every kind of entity under the sun. We have a much more modest, but still ambitious, proposal:

Let’s use the open identifier systems we already have effectively, consistently, and to mutual benefit

Many of the open components we need to map the terra incognita are already in place, or under development. There are Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs) for research content, provided by organisations such as Crossref and DataCite. There are ORCID iDs, a globally established open identifier for researchers. The Organisation Identifier initiative has the potential to link up the disparate and partial systems that identify organisations today, helping us to connect individuals to the organisations that educate, employ, resource, and fund their research.

As research increasingly moves online, we have the opportunity to use digital technologies to automate, remove friction, and eliminate the duplication of effort. Open persistent identifiers can help simplify processes and enable the reuse of information — but only if we use them properly.

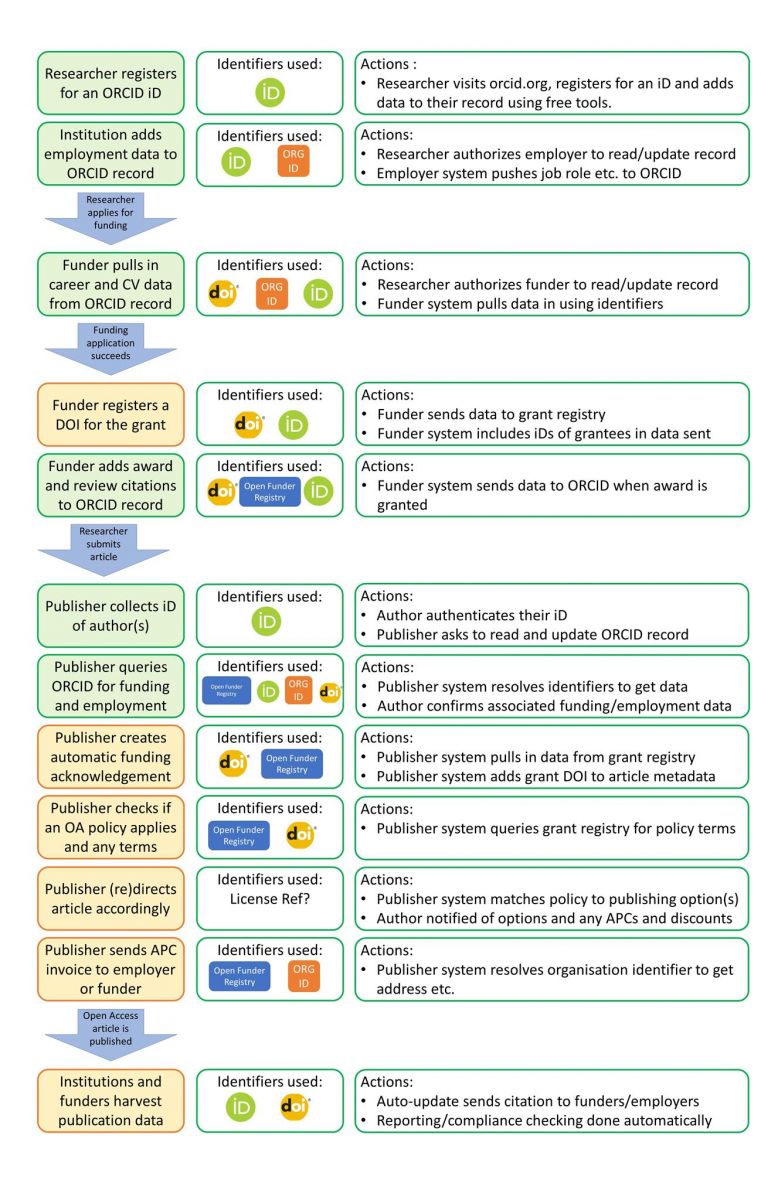

We’ve mapped out below how this could look in one common workflow — submitting a manuscript to a journal. The green items and activities on the left are already in place; the orange ones are not, yet, but many are under discussion or being actively developed.

There are many other researcher workflows that would benefit from increased use of persistent identifiers, but to make this happen, everyone must play their part. We are on a mission to make this vision a reality – and we hope you’ll join us! Our PID Perfect campaign will be launching later this year. Look out for more information and feel free to contact us in the meantime if you’d like to get involved.