This guest post, by Andrew Dunning (a lecturer in the Faculty of Information, University of Toronto, Canada) explains in simple terms why researchers would want an ORCID record, how best to set one up, and what they can then do with it.

There’s a lot of information about your research floating around on the Internet. But it’s not usually doing you much good, because it’s so hard to find and connect with a single person. I can’t tell you how many times I have found an interesting article and wanted to find what else that person had written, and had to hunt up and down for that information. You’ve done the work of producing that research: make it easy to find!

ORCID is the first truly sustainable research portfolio. It saves you time by reducing the amount of work you have to put into re-entering citations and funding figures, and it supports the entire academic ecosystem. Instead of trying to be a repository for all your research files, ORCID simply links to wherever they live. You won’t be pestered with daily emails, you don’t have to be a technical wizard, and you’re in control of your privacy – you can just get on with what you care about.

With ORCID, you can harness the public records about your research. It allows you to link all this data together in a handy page about yourself that you can then share publicly with others, or keep to yourself. Trusted organizations can also integrate with ORCID, and you can choose to share the information on your record with them. I use my iD as an online master list of all my publications: it’s the perfect link to give anyone who wants to read what I’ve done recently, introduce me at a conference, or consider me for a new position. Since the source of the information is clearly shown, it’s easier to confirm that I’m not making it up. If you’re moving around constantly as an early-career researcher, journals can include a link to your ORCID page instead of (or as well as) your email address, and readers will still be able to find you when you’re booted off your last institution’s network. And a growing number of universities allow you to use the information in your ORCID record to create your annual reports. In short, ORCID saves time for both you and your readers – Times Higher Education calls it ‘the new CV’.

The data you bring together also helps the scholarly community as a whole. Unlike most online research profile systems, ORCID is not-for-profit. It doesn’t track you or sell your data. By default, everything you add to your ORCID record (other than your email address) goes into the public domain. If you want to keep something private, it stays that way unless you choose to change it. Instead of lining someone else’s pocket, you’re contributing to shared knowledge about your research when you use ORCID.

ORCID has lots of tutorials to help you get started. Here’s the one-page, three-step version.

1. Get an ORCID record

ORCID gives you a permanent number – like an ISBN, but for people – that can be used to distinguish yourself from other researchers, even if they have the same name, for your entire career. To register for ORCID, all you need is one version of your name, a password, and a valid email address.

If you’ve submitted an online funding application or an article recently, there’s a good chance that they already asked you to sign up – a growing list of publishers require it, as do many funders. If you’re not sure if you have an iD, try putting in a couple of your email addresses (past and present) first thing before you submit the form: the system will immediately tell you if it already has you on file. If you accidentally create more than one ORCID record, not to worry: you can easily remove duplicate records.

Once you have an iD, the first thing you’ll want to do is to add all the email addresses you use in your research (you don’t have to make them public) to ensure that you don’t accidentally sign up again with one of them or lose access to your account. If you don’t feel like remembering yet another password, you can sign into ORCID with your institutional login, or your Google or Facebook accounts.

2. Add your work to ORCID

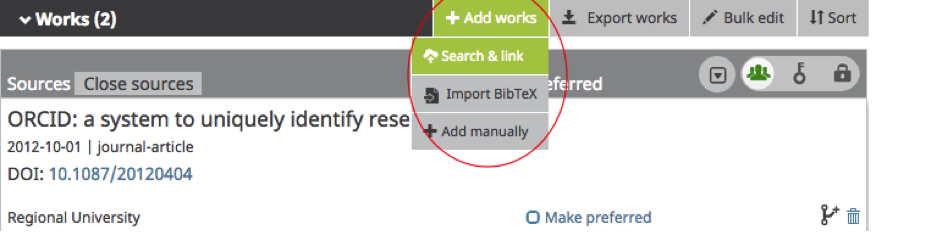

The ORCID magic begins when you start to add information to your record. You don’t have to type everything manually: just use the ‘Search & link’ button.

The ORCID magic begins when you start to add information to your record. You don’t have to type everything manually: just use the ‘Search & link’ button.

Use the Search & link tool to import all sorts of records about your research.

This will show you all sorts of tools that you can use to add works to ORCID. If you mostly publish in English, start with these:

- If your research is published in a major journal, Scopus is a satisfying place to start: this is a database of both large publications and who refers to them. Open the page, find yourself, and add the information to ORCID. If you’ve worked in more than one place, chances are good that you’ll be listed more than once. You can ask to have these records merged when you add them to ORCID.

- CrossRef is the largest registry of formal research published online with a DOI (a Digital Object Identifier). They almost certainly list your articles if they’re available online through a professional publisher. When you open the linking tool, it will search for your name, which isn’t always effective: you might try searching for the title, or if you know the DOI, you can search for that directly. If you see one of your works that you already got from Scopus, add it anyway: CrossRef data is sometimes more up-to-date, and ORCID should automatically merge the two.

- DataCite is another registry of DOIs, focused on research data that doesn’t fit into a formal publication. If you add anything to FigShare, for example, it will be listed there. In addition to searching for your name, you can go into the settings and allow it to add new works to your ORCID record automatically.

If you’re still missing some of your works, you can move on the other linking tools specializing in certain subjects or countries: for example, Europe PubMed Central covers medicine, and the MLA International Bibliography indexes literary scholarship. BASE, the Bielefeld Academic Search Engine, is great for finding publications that are online but don’t have a DOI (such as most theses). If you already have your works in a citation manager such as Zotero or Mendeley, ORCID can also import a BibTeX file.

3. Harness ORCID for your research

ORCID can save you time when you use your iD when applying for funding, jobs, and publications in systems that support it. Submitting an article using your ORCID iD means that you probably won’t need to remember yet another password for the submission system. For publishers that collect iDs and pass them to Crossref – ranging from The Royal Society to the Open Library of Humanities – you can allow automatic updating of your ORCID record with your new publication when it’s out.

You can fill out as much or as little of your ORCID record as you want. There’s another linking tool for adding funding that covers many national research councils and large funding agencies. You can also list your peer review activity by tracking it in Publons and setting it to synchronize with ORCID.

If you have a friend or research assistant willing to update your record, you can add them as a trusted individual without giving them your password.

There are also lots of clever online services that integrate with ORCID to do interesting things for your research:

- Preserve your work online using Zenodo or the Open Science Framework.

- See which of your articles could be made open-access using Dissemin.

- Publish ideas and data informally using FigShare or the Journal of Brief Ideas.

- Collaborate on scientific papers and submit them directly to journals with Overleaf.

- Create plain-English summaries of your articles using ScienceOpen or Kudos.

- Find where your work is being talked about on Twitter with ImpactStory.

- Link your research listed in the Web of Science database to your record by signing up for ResearcherID synchronizing it with ORCID.

- Get suggestions for funding applications based on your publications with Pivot (if your institution subscribes).

- Tell libraries that you’re on ORCID by using the Search & Link tool for ISNI, an ISO standard for distinguishing creators from each other. (If you’ve published a book, you probably have an ISNI.)

Support for ORCID is growing quickly in research software, and it will only get better as more academics and developers adopt it.