2021 is the fifth anniversary of ORCID’s Trust Program and we’re celebrating with a series of blog posts that outline our thinking about how we balance the sometimes-competing priorities of researcher control and data quality, while adhering to our values of openness, trust and inclusivity.

As adoption of ORCID grows, we are constantly presented with new opportunities and challenges as we seek to deliver our mission of enabling transparent and trustworthy connections between researchers, their contributions, and their affiliations. We’ve learned that in our efforts to achieve our vision of a world where all who participate in research, scholarship, and innovation are uniquely identified and connected to their contributions across disciplines, borders, and time, “trust” is the linchpin. How ORCID thinks about and approaches trust — individual control, accountability via public scrutiny, and integrity via strict provenance tracking — has changed very little since ORCID was first founded, or since we launched our Trust Program in 2016. The fact that we are community-built and governed by a Board of Directors representative of our membership ensures that we continue to have the trust and buy-in from the community we serve.

This blog post is the first in a series celebrating five years of the ORCID Trust Program. In this post we aim to reacquaint users with our Trust Program and clarify our thinking about how we balance the sometimes-competing priorities of researcher control and data quality, while adhering to our values of openness, trust and inclusivity. We’ll discuss emerging challenges presented by ORCID’s growing participation levels (yes, we’re talking about spam). You’ll learn what kind of spam we experience, what we’ve been doing to address it, and why it’s more of an annoyance than a practical barrier to ORCID’s use. We’ll also talk about our approach to handling fraudulent claims in ORCID records and resolving disputes. Finally, we’ll cover how trust markers in ORCID records, added by ORCID member organizations, allow ORCID data users to determine for themselves which records to trust.

In subsequent posts we’ll cover how researchers can optimize their own ORCID record to ensure it provides maximum value, how institutions can encourage their researchers to engage with their ORCID integrations, and we’ll help ORCID data users interpret information they may find in the ORCID registry.

Still keeping the researcher (contributor, scholar, user) at the center of all we do

In 2016, ORCID engaged with privacy and data security experts from the community to help us review and refine the practices and policies underpinning the trustworthiness of ORCID. From this work, we developed the ORCID Trust Program to provide transparency about the controls, policies, and practices we put into place to ensure connections are controlled by researchers and the source of each connection is openly articulated. Like everything we do, the ORCID Trust Program is rooted in ORCID’s 10 Founding Principles, two of which directly address our commitment to researcher control.

The definitions of researcher, scholar, and contributor evolve over time and can vary from field to field and country to country. Regardless of how our registry users think of themselves, ORCID has always been committed to keep them at the center of everything we do. Researchers will always be able to create, edit, and maintain an ORCID identifier and record free of charge. Researchers control who can see their data and who they share control with — to write to and read from and update their records — and for how long.

ORCID was meant to solve name ambiguity

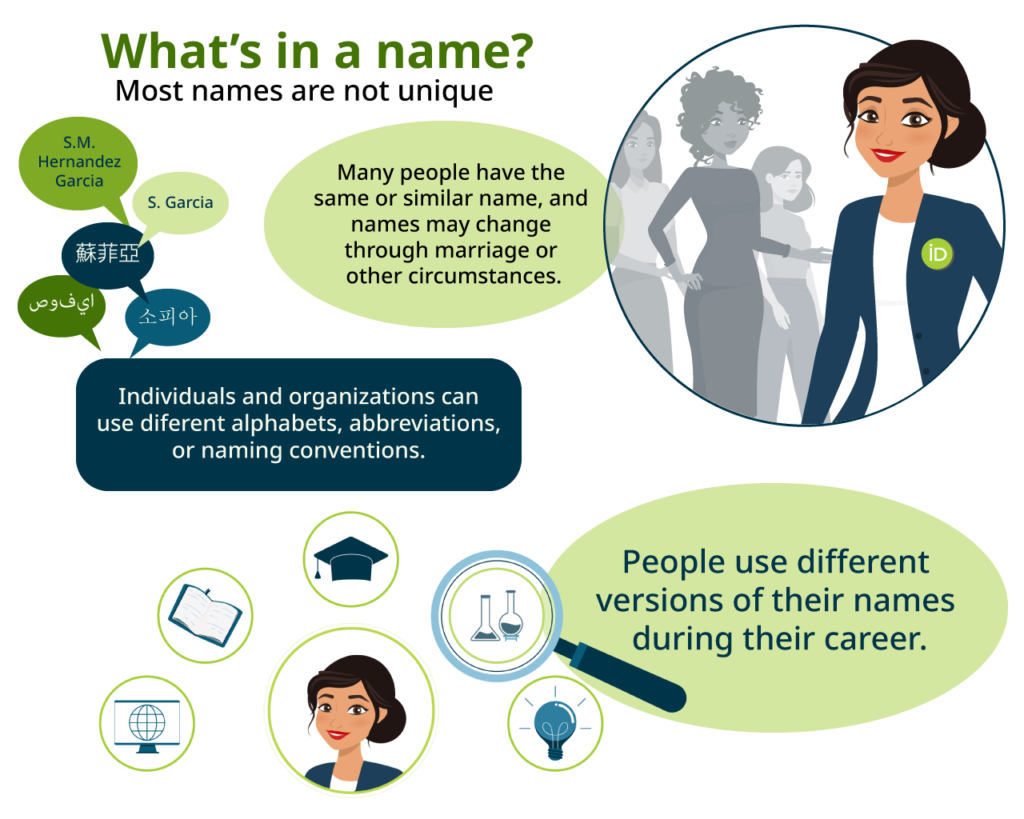

As individual as we all are, our names are really not that unique, and attempts to link research activities and outcomes to a person’s name have led to endless confusion in the past. Even in the same discipline, hundreds or even thousands of researchers can have the same or similar names. There can be endless variations of names, which can change over time: Sofia Maria Hernandez Garcia, Sofia Garcia, S.M. Garcia, S. Hernandez Garcia. Researchers learned a long time ago that names are not enough to ensure credit for their work.

ORCID, as a name-independent person-identifier, was founded specifically to help solve the problem of name ambiguity in research, and to enable transparent and trustworthy connections between researchers, their contributions, and their affiliations.

To meet this use case, the important characteristics of ORCID iDs are that they are unique, persistent, and controlled by a single real-world individual. Unique so that people with the same name can be distinguished from one another; persistent so that one individual can maintain the same ORCID iD throughout their entire career; controlled by a single individual so that users of ORCID data can be reasonably confident that the data contained in the ORCID record is the data that the record-holder wishes to present to the world about themselves. It is not necessary for our use case for the availability of ORCIDs to be restricted to a specific class of individuals, nor for some authority to control who may obtain an ORCID. And, as we shall see later, imposing these constraints would actually make it harder for us to achieve our goals whilst maintaining adherence to our values.

It is important to reiterate that our intent has always been to provide a mechanism by which researchers can connect with trusted organizations that update their records through validated workflows, not to be a mechanism by which researchers are validated as researchers simply by having an ORCID iD.

Put another way, the existence of an ORCID record in itself isn’t indicative of the validity of a researcher any more than the presence of an ISBN on the back of a book assures that that book is a good read. Much like the content of the book that determines its quality, the content of the data in an ORCID record can tell you a lot about its trustworthiness. In the case of ORCID, we provide a mechanism for users of ORCID data to judge the origin and trustworthiness of information in ORCID records for themselves by recording and disclosing the provenance of each and every assertion present in a record.

ORCID is open to everyone who may find ORCID useful

For simplicity we often use the word “researcher” when referring to an ORCID record holder, but remember the “C” in ORCID stands for “contributor” — our users hail from a far broader context than just one word can encompass. In fact, ORCID enables everyone who might find benefit from using the ORCID Registry to be able to obtain and use an ORCID iD. Any rigid definition of who would “qualify” for an iD would likely unintentionally exclude people for whom an ORCID iD would be useful due to the wide diversity of circumstances researchers find themselves in around the world. Moreover, with around 10,000 new records created every day, it would pose an enormous drain on the resources that the scholarly community collectively contribute to fund ORCID in trying to enforce such pre-validation, with little advantage.

It is specifically by not setting any such criteria on who can register for an ORCID record that we ensure inclusivity and encourage the persistence of ORCID iDs. We want to encourage budding researchers to establish their ORCID iDs as early in their careers as possible, as undergrads, or even secondary or high school students — even if they have not yet created any formally recognized research outputs. Similarly, we don’t wish to exclude independent researchers such as citizen scientists or those currently unaffiliated with a formal academic institution due to career breaks or retirement.

A natural consequence of this approach is that bad actors may choose to self-assert information in ORCID records that is false, either in the pursuit of financial gain or for the purpose of committing academic fraud (or both). We believe that it is our commitment to these values of openness and inclusivity that has resulted in the broadly adopted, open repository of user-generated data that ORCID has become. The flip side to that openness and inclusivity is the inevitable inclusion of individuals who may not be considered by the broader scholarly community to be legitimate researchers and that some of the data that they choose to share on their records may not be considered by others to be objectively true.

With over 11 million records at the time of this writing, it would be surprising if we were able to boast no records of questionable scholarly content or quality, and that is clearly not the case. We find that problematic records come in two main types: SEO or link “spam”, and blatant attempts to claim false academic records. We have distinct approaches to handling each case, as we will further detail below.

Search Engine Optimization is not an ORCID use case

In no small part due to our success in achieving adoption and wide use by the scholarly community, orcid.org has amassed not inconsiderable engagement on the internet: we rank among the top 5,000 sites globally according to Alexa.com. As a result, like most other high-traffic sites which allow user-generated content, we are a honeypot for those attempting to game search engine algorithms by exploiting our relatively high influence on search engine rankings (otherwise known as “link juice” or “domain authority”) to attempt to boost the ranking of their own sites. This practice is known as “link spamming” or “SEO (Search Engine Optimization) spamming” and is often perpetuated by so-called “link farmers” or “black-hat SEO operatives”.

Ironically, this exercise is largely futile, as links to other sites from ORCID records are tagged with “NoFollow” codes. For the most part, this prevents these spam records from lending increased SEO value to the linked sites in the first place. Nevertheless, the spamming continues — we suspect because link farmers are compensated according to the volume of spam created rather than the value of the outcomes achieved. Too bad for the would-be link farmers’ customers, but SEO optimization for kitchen sink businesses has never been a use case for ORCID!

An endless game of whack-a-mole

Link spam, while a nuisance, doesn’t affect records surfaced in the authenticated workflows that we encourage, as a spammer has no incentive to use their records to sign in or connect to legitimate scholarly services and systems. Even so, we understand why these records raise alarm and cast doubt on the overall value and trustworthiness of ORCID.

We work hard to constantly monitor for and “lock” suspected spam records, such that they are not visible to anyone other than the record holder. We regularly run heuristics to detect spam records, and our user support team typically locks thousands of records every month. We also take standard measures to limit spam from being created automatically by bots such as requiring completion of a CAPTCHA prior to record creation.

Unfortunately, our current heuristic approach is very labor intensive — as it can result in false positives, we carefully review each suspected spam record to ensure that we are not inadvertently impacting researchers who might be working on topics that coincide with the “interests” of spammers, such as cyber currency or human sexuality. Considering the growth of the ORCID registry, we are in for an endless game of whack-a-mole, but we are up for the challenge.

We have recently experimented with a Machine Learning approach to detecting spam, which is yielding very promising results. We believe such an approach would reduce the need for manual review and allow us to lock spam records on a more timely, continuous basis. Whilst not yet firmly on our roadmap, we hope to be able to announce more progress on this in the coming year, subject of course to a thorough privacy assessment. As an interim step, we are taking measures to improve the relevance of our search results in order to mitigate the impact of spam records on legitimate users.

Sunlight is the best disinfectant

The second type of problematic record is more troublesome, but fortunately much rarer. This type involves blatant attempts at academic fraud and comes from people who create fake or deceptive ORCID records either in the misguided belief that merely having an ORCID iD conveys some degree of legitimacy, or in an attempt to falsely claim credit for the work of others. This behavior is objectionable and clearly prohibited by our terms of use.

As a neutral, inclusive infrastructure provider, however, it would not be appropriate for us to take an editorial position on the veracity of claims in ORCID records, nor would it be feasible for us to proactively curate the ORCID registry or monitor for fraudulent records. Instead, it is the very openness that has been baked into ORCID since its foundation that enables the claims made by record holders to be held up to public scrutiny, in turn permitting the community to monitor and report any concerning claims.

If you have concerns about the data in another person’s ORCID Record or the intent of the record holder, we recommend as a first course of action that you contact that person directly. Failing that, our User Support team can help resolve the complaint following the steps outlined in our Dispute Procedures. When we receive a report of suspicious data, the User Support team initially works with the disputing party and the record holder to resolve the issue via good faith dialogue. On the rare occasions when this is not successful, we follow the escalation steps outlined in our dispute procedure and ultimately, we reserve the right to lock the incorrect record and mark it as disputed if the record holder will not agree to make corrections. We maintain a log of when and by whom data in the registry are added, edited, or deleted to aid in this process.

Researcher control and high-fidelity connections engender trust

Since ORCID’s foundation, there has been a school of thought that ORCID — or other authoritative third parties — should arbitrate what data can be placed in an ORCID record. There are, after all, many other biographical databases that work this way, following the traditional “authority file” approach. And if that kind of highly managed and curated data is best for your use case, we recommend that you work with one of them.

However, ORCID is and was always meant to be different. We’ve found that adhering strictly to our Founding Principle of researcher control has been essential to winning the trust and participation of the data subjects themselves, and this in turn has been essential to the wide uptake and utilization of ORCID by researchers across the globe, even if this means letting go of the idea of central authority.

Authoritative metadata still plays a very important part in ORCID however. Rather than one party centrally maintaining the data in ORCID records, we have implemented a distributed trust model which allows reliable and trustworthy data sources of all manners and types to be connected, with the record holder’s permission, to their ORCID record. We maintain strict metadata about the provenance of each and every assertion in an ORCID record and disclose this in the Registry UI, via our API, and in our public data file. This way, users of ORCID data can determine for themselves, which assertions they trust, and which kinds of assertions they consider to be “trust markers” for their specific use case — for example affiliations which have been authenticated by research institutions or publications which have been authenticated by publishers.

Our authenticated workflows ensure that a record can be connected to an activity, idea, or organization only with the direct permission of the record holder. Moreover, only ORCID member organizations authenticate claims in ORCID records, ensuring that they are subject to our scrutiny and held to the terms embodied in our membership agreement.

Once established, these high-fidelity connections create a self-reinforcing loop: in workflows where researchers derive a lot of benefit from having an ORCID iD, for example by avoiding repetitive data entry, they are more likely to engage with and connect their records, leading to more complete and accurate population of ORCID records with reliable metadata. We’ve found that while 48% of records overall have some item of metadata attached to them, that number goes up — to 56% — for records connected to at least one external system. Further, for records connected to systems in places with coherent national policies and support for PID infrastructure, for example Australia, the number increases to 88%. One of our key priorities for the coming years is to encourage the adoption of national PID strategies more broadly, and the integration of ORCID with key national research infrastructure in places where that isn’t the case today.

Next up: interpreting “trust markers” in ORCID records

ORCID’s foundational commitment to researcher control has proven essential to winning the trust and participation of researchers, which has in turn been essential to the wide uptake and utilization of ORCID by researchers and organizations across the globe. Like most other high-traffic sites which allow user-generated content, our success has made us an attractive target for those who would create records in the pursuit of financial gain or for the purpose of committing academic fraud (or both). We discussed our distinct approaches to handling each case, as well as plans we have to improve our abilities to handle spam in the future.

In order to balance the sometimes-competing priorities of researcher control and data quality, ORCID utilizes a distributed trust model which allows reliable and trustworthy data sources to be connected via authenticated workflows to an ORCID record with the record holder’s permission. Further, by recording and disclosing the provenance of each and every assertion present in a record, we provide a mechanism for users of ORCID data to judge the veracity and trustworthiness of information in ORCID records for themselves.

Helping users understand how to interpret information stored in an ORCID record is an element of our Trust Program. In our next blog post in this series, we continue our five year anniversary celebration of the ORCID Trust Program by introducing the concept of “trust markers” in an ORCID record and discuss how users of ORCID data can determine for themselves which assertions they trust, and which kinds of assertions they consider to be trust markers for their specific use case.

Associated Links

- Assertion Assurance Pathways: What Are They and Why Do They Matter?

- ORCID Trust

- Auto-updates: time-saving and trust-building

- Building a Robust Research Infrastructure, One PID at a Time

- Open Access in Context: Connecting Authors, Publications and Workflows Using ORCID Identifiers

- Using ORCID, DOI, and Other Open Identifiers in Research Evaluation

- What’s So Special About Signing In?